The New Generation in Hybrids |

The reviews are in, and even the supporters of Justin Lin's "Fast and the Furious 3: Tokyo Drift" can't get beyond the fact that it's merely a generic Hollywood auto racing film. APA looks for subversion within the formula.

drift, v.

1. To be carried along by currents of air

or water.

2. To move leisurely or sporadically from

place to place, especially without purpose.

Universal takes its

"Fast and the Furious" franchise to the streets of Japan, hoping to

charge the profitable but repetitive series with a bit of exotic variation.

Sequels appeal when they straddle the expected and the unexpected, delivering

the original’s formula in new packaging so the consumer doesn’t notice how

redundant the whole experience really is. The inclusion of the Japanese racing

style "drifting" -- where tires skid as they make sharp turns at high

speeds -- is merely a fresh substitution into a tested formula. Cars plus kung

fu equals box office champion. [Editor's

note: Or rather, a still-impressive third-place showing in its opening weekend

returns]

Enter Justin Lin.

Already a veteran of Asian American independent cinema (having directed or

co-directed the landmarks Better Luck

Tomorrow and Shopping for

Fangs), the young filmmaker has set the bar high as he steps into

Hollywood. His mainstream debut Annapolis fizzled commercially and critically. The

Fast and the Furious: Tokyo Drift should have been a cakewalk to

blockbuster success. The car racing formula shoots itself; Lin’s role is to sit

back and let the cars do the talking while Universal claims racial diversity

behind the camera as it collects the cash.

Lin’s willing to play

their game, but he knows there’s plenty of territory to be won within the

formula, as long as it still makes money. Tokyo

Drift is an above-average Hollywood teen action with two or three

well-edited and well-shot race sequences that rival any in the series thus far

(and well-surpassing last year’s disappointing Initial D). The handling of space and locations is very

strong, particularly in one scene set in a parking structure and another in the

mountains. Lin has successfully recreated the generic template to please the

studio and fans of the first two films, but he knows that just as there’s more

than one definition to the word drifting, there can be meanings to the car

racing genre beneath the superficial. The result is a film that doesn’t tackle

serious issues, but sinks them into the formula itself. For that reason, The Fast and the Furious: Tokyo Drift could be the first Hollywood blockbuster to reflect an Asian American ethos.

The Outsider

Lucas Black plays

Sean, a no-good, Southern-accented, high school loner from Arizona whose

car-racing mischief has forced him from town to town to escape the law. This

time, he’s chased to Tokyo, where his army dad reluctantly takes him in --under

the condition he doesn’t touch a car again. Sean’s an outsider, the prototypical

hero/loner of the American myth. Like the cowboy, he rolls into town and saves

the day. He lives by morals, but they’re his morals and nobody, be it his

father or the rival gang, can stop him.

The superficial

variation here is to transplant the outsider to the streets of Tokyo. His sense

of morality remains, but what makes the film special from a cultural

perspective is that we watch Sean assimilate to Japanese culture without the

racist American self-smugness seen in Lost

in Translation. No peering down on short Japanese; in fact, it

often looks like the 5'10" Black is framed to look the same size as the

Japanese men around him. And no offensive jabs at Japanese culture. He’s a fish

out of water, but the joke is, the fish learns to live without the water. Sean

first sighs that he has to wear a Japanese school uniform, but it never becomes

an issue again as he discovers there’s nothing intrinsically wrong with it. He

at first stares at Japanese food in confusion, before he realizes it’s pretty

good. He’s shocked that he’s expected to understand Japanese at school, but

rather than arrogantly rejecting the culture, he learns the language so he can

interact with his host society, which is far more than we can say about

characters (and producers) of Hollywood films today.

Tokyo Drift contains a

surprisingly sensitive portrayal of the community of army brats in Tokyo.

There’s an understanding between them that they need to stand up for each

other, and that they’re outsiders together. Sean asks an attractive Australian-accented

classmate, "Where are you from?" She replies, "From here."

He smiles, "No, I mean, where are you from originally?" She shoots

back, "Does it matter?" Ethnically, racially, culturally, they’re all

drifters, obsessively defining themselves as not quite inside and not quite

outside. If they were born or raised in Tokyo and speak Japanese, why are they

perpetually labeled as foreigners because of their skin color?

The Cars

"The Fast and

the Furious" series has been Hollywood’s most successful line of car porn

ever, and even reluctant viewers go into the theater under the assurance that

"there will at least be great cars to look at." In these films, cars

are feminized and exoticized. That they’re sexy and shiny is as important as

their speed. Lots of fetishistic close-ups on decals, rims, and grills,

accompanied by hip-hop music and scantily clad models grinding in slow motion.

The fetishism is all

present here, and while the underlying gender problematics remain, what’s new

in Tokyo Drift is the fetishization

of another culture’s vehicular sexiness. While the first film in the series

made a point of ogling at quintessentially American muscle cars like the Dodge

Charger and the Ford Lightning, Tokyo

Drift presents a culture shock of brightly colored smaller racers.

Sean calls them "toys" when he first sees them, before he realizes

that the smaller sizes are what enable them to "drift." Also,

everyone -- even the army brat played by Bow Wow -- is infatuated with this

line of cars, and there doesn’t appear to be any alternative. Asian culture

suddenly isn’t just different; it’s a source of envy and genuine admiration and

desire.

The Mentor

The outsider needs a

mentor to help him navigate the inside. Here, he’s Han (played by Sung Kang),

thematically the most interesting character in the film because he’s an

outsider who looks like an insider. When we first see him, we assume he’s one

of a gang of wannabe-yakuza (led by DK, played by Brian Tee), but unlike the

villains, he speaks with an American-accented English. As an Asian American, he

empathizes with Sean because he too was once an outsider in Tokyo. It’s a

revolutionary move by the screenwriters: on the boundary between East and West,

the Asian American is identified as American rather than Asian.

The Training

Toward the beginning

of the auto racing film, the hero must lose. After a rigorous training period,

he will emerge able to redeem himself. In Tokyo

Drift, the training consists of un-learning an American style of

racing and replacing it with the style of the Tokyo underworld. As he learns

the hard way, zipping fast through cramped spaces and sharp turns is

ridiculous. To win, he needs to learn to drift, a fundamentally different form

of driving that relies on momentum and feeling rather than sheer speed.

However, unlike say, The Karate Kid,

which equates martial arts training with tapping into ancient Eastern wisdom, Tokyo Drift equates drifting with

becoming oneself rather than becoming Japanese. It’s significant that it’s the

Sung Kang and Bow Wow characters that cheer him on in these training sequences.

"It’s not ‘wax on, wax off,’" advises Han, citing Mister Miyagi’s

famous mantra. Instead, drifting is about the driver’s ability to feel the road

in a new way.

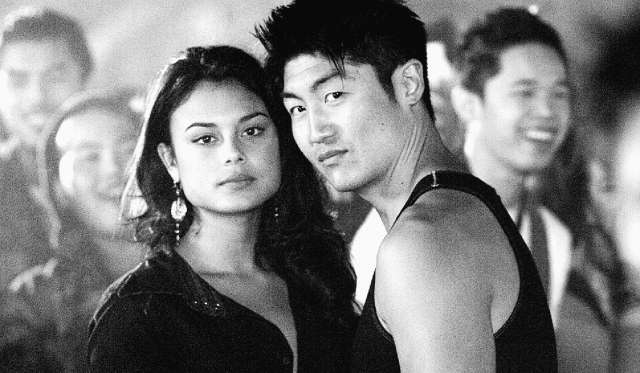

The Girl

There’s gotta be a

girl, and she has to love cars. Here, it’s the Aussie Neela, played by newcomer

Nathalie Kelley. She’s also an outsider, and in many ways, she, like Han,

advises Sean on how to adjust to the Tokyo underground. And like so many of the

characters, she’s a drifter in both senses of the word. In the film’s

surprisingly effective romantic interlude, she takes Sean on a balletic

mountain ride, drifting down the mountain like an elegant skier. Neela displays

complete control over drifting, but without the coarse and dangerous displays

of machismo. For Sean, the ride down the mountain is the ultimate car porn

seduction: the feminized vehicle takes the man for a ride rather than vice

versa.

Not surprisingly, the

logic of the races still positions women as observers rather than participants

(unlike 2 Fast 2 Furious which

featured Devon Aoki and her pink rice rocket). Off the track, women -- Japanese

and non-Japanese alike -- are trophies for the men ("the winner of the

race gets me" says a woman in one of the film’s stupidest moments). But

what is surprising is who gets the trophies. I feared that Sean’s reward for

his Tokyo victories would be a nice Japanese girl, but that’s never the case.

("Why don’t you get yourself a Japanese girl like all the other white guys

here?" asks Han, in a self-conscious play on America’s culture of Asian

fetishism.) It’s also empowering to see the Asian American Han as a sexual

aggressor, tonguing random models in a hip backroom dance club and using his

drifting skills to woo the digits from some unsuspecting passerbys. It’s

unfortunate that Asian American male sexuality has to come at the expense of

female dignity, but I’ll take what progress I can get provided we acknowledge

that there’s still plenty of territory in the genre’s template that needs

reworking.

It’s also unfortunate

that Neela needs to be saved by Sean from an evil Yakuza whose poor English

makes even an American viewer yearn for subtitles. At best, we can interpret

her preference for Sean to be a cultural drifter’s attraction to another

"in-between" person, but at worst, this is simply another case of

yellow peril paranoia.

The Showdown

As the training comes

to a close, there needs to be a transition into the final showdown between the

hero and the villain. The hero needs to confront certain personal demons and

dilemmas (frequently involving the girl) and learn to make the necessary

adjustments before suiting up for the big race, which he inevitably wins. (In a

Hollywood racing film, that’s no spoiler.)

In Tokyo Drift, Sean finds his formula for

success in the car he chooses to ride against his Japanese nemesis. With the

help of his friends, Sean fixes up a beat-up Ford Mustang and equips it with a

Nissan engine. With an American style and a Japanese heart, Sean exemplifies

the second definition of drifting. Culturally, he’s in-between two cultures and

he wins because he takes the best of both worlds to the track, turning his

hybridity from a liability into a strategy.

The race itself is

not a showdown of East and West, where Sean wins because of his American

inclination for speed. In a great article by Jeff Yang, Justin Lin is quoted as

saying, "In the original script for this film, Sean, the movie’s hero,

wins the big race by kicking in a hidden nitrous tank and blowing past the bad

guy. Anyone who knows anything about drifting would have just laughed his ass

off at that. It just makes no sense: You can’t win that way. Drifting is not

about power." In other words, Sean wins because he’s absorbed the culture

of drifting and learns how to make it work for him.

The Comic Outro

After the showdown is

the obligatory comic outro. Tonally, the film lightens up a bit, the humorous

sidekicks make their reappearance, the music switches into party mode, the girl

winks at the hero, and there’s a comic punchline that sends the audience out

with a sense of closure but also prepared for another sequel.

I can’t divulge what

happens in these closing moments. (In a Hollywood racing film, this would be

the spoiler.) Let’s just say one of the guys Han used to kick it with makes a

cameo in an American muscle car, and he cockily thinks he’s ready for the Tokyo

racing scene. Now Sean’s the mentor.

Drifting’s about

crossing boundaries, defying categorization, and unlearning prescribed

traditions to find one's own self. The

Fast and the Furious: Tokyo Drift is about a community of drifters

that prove it’s more exciting to be in-between cultures than simply either

"Japanese" or "American." Though there isn’t an Asian

American in sight, the film’s comic outro unexpectedly makes it cool to drift

the line between outsider and insider.

Date Posted:

6/15/2006